Information For Faculty

Join us in providing access to students!

Welcome to the pivotal partnership for fulfilling our institution’s commitment and responsibility to ensure that students with disabilities have equal access to UH Maui College’s programs, activities, and services. You, your student, and our Disability Services Office constitute the team that can address your student’s disability access needs with confidentiality, respect, and effectiveness.

*Please note that student situations vary widely; the best way for us to appropriately serve our students is to treat each student and situation on a case-by-case basis.

- Identification of Students with Disabilities

- Faculty Responsibilities

- Providing Test Accommodations

- Note Taking and Note Takers

- Disability Awareness

- Understanding Disabilities and Structuring for Success

- Accessibility

- Universal Design

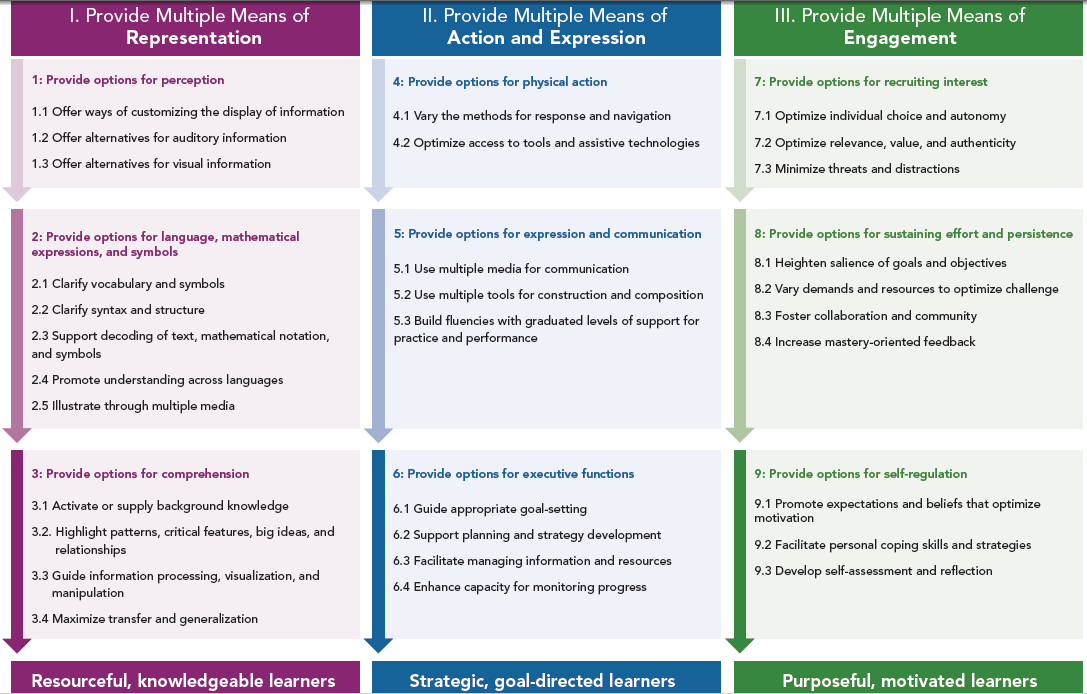

- Instructional Design Using the Principles of Universal Design

- Equal Access: Universal Design of Instruction (video)

- General Tips that Facilitate Student Learning

bottom of Information for Faculty

BACK TO TOP

Identification of Students with Disabilities

You are likely to learn of your student with a disability in one of three ways:

-

- Identified Student

The student will provide you with a confidential, disability accommodation letter from the Disability Coordinator. These accommodations are based on documentation that was presented and reviewed by the Disability Coordinator. This letter will advise you of what accommodations may be needed in your class in order to provide equitable access.

Disclosure of disability status is voluntary on the part of students. For a variety of reasons, some students decide not to disclose their disability status to faculty members. In situations where the student has not disclosed their disability, you are under no obligation to provide accommodations.

-

- Non-Identified Student

A student may privately disclose his/her disability status to you and request various accommodations. If a student requests accommodations, you should have been provided with a letter from the Disability Coordinator. If you have not received a letter, please inform the student of the proper procedure.

*There can be legal consequences for provisions of accommodations to a student who is not registered with the Disability Coordinator.

-

- Your Speculation

If you suspect that a student has a disability, please refer them to a counselor for academic advising. It is NOT appropriate to make a referral to the Disability Coordinator if the student has not disclosed their disability.

bottom of Identification of Students with Disabilities

BACK TO TOP

Faculty Responsibilities

Faculty members are to work in conjunction with the Disability Coordinator in providing approved accommodations and support services in a fair and timely manner. Students should initiate a meeting to discuss the accommodations with faculty.

- Include an accommodation statement on every syllabus, and read aloud to students during the first week of class.

- Discuss with the student the accommodations or arrangements requested by the Disability Coordinator on the accommodation form as soon as possible.

- Contact the Disability Coordinator if you have any concerns about the requested accommodations. The student’s documentation is considered a medical record, and therefore, does not qualify to be part of the student’s records and is not subject to faculty inspection.

- Assure the confidentiality of any information relating to a student and a disability. At no time should the class be informed that a student has a disability.

- Ensure that the student with a disability is held accountable for the mastery of material as you would any other student (although mastery may be demonstrated in a different manner).

- Ensure that testing will occur in an appropriate manner. If the test will be administered in a location other than the classroom, ensure all directions are communicated to the test administrator. Coordinate test delivery and return with the test administrator.

- Shred all documents when the student is either no longer in your class or when the session is completed.

To have both a syllabus statement as well as a verbal announcement of the faculty member’s commitment to welcoming students with disabilities is highly desirable. Please see the sample syllabus statements below regarding disability access, and feel free to alter this statement to meet the specific needs of your course.

1) If you have a disability and have not voluntarily disclosed the nature of your disability and the support you need, you are invited to contact Shane Payba – Acting Disabilities Services Counselor at 984-3496, Videophone relay service at 1(200)203-9685, TTY Relay Service at 711 or 1(877)447-5990 or the Text Telephone (TT) relay service at 643-8833.

2) Reasonable accommodations will be provided for students with documented physical, sensory, systemic, cognitive, learning and psychiatric disabilities. If you believe you have a disability requiring accommodations, please notify Catherine Taylor – Disability Coordinator at 984-3227, Telecommunication Device for the Deaf (TDD) 984-3741, or the Text Telephone (TT) replay service at 643-8833. The Disability Coordinator will verify your disability and provide the course instructor with recommendations for appropriate accommodations.

bottom of Faculty Responsibilities

BACK TO TOP

Providing Test Accommodations

Students with disabilities may need reasonable accommodation in test taking, and your assistance is needed. Test accommodations are essential components of our institution’s commitment to guaranteeing equal access to students with disabilities as mandated by federal and state laws.

- Students have been asked to request from the Disability Coordinator their accommodation letter at least one week prior to the test date. This letter will show the specific testing accommodations the student qualifies to receive. Students are also asked to approach you about their need to take the test with accommodation(s).

- Generally, testing is done in the classroom or at The Learning Center (TLC), though other appropriate locations may be arranged.

- Students are expected to take their tests at the same time as their classmates.

- Any alternate arrangements must be cleared with you first.

- If TLC is used as the test location, you are responsible for dropping off and for picking up the testing materials (at TLC). There, you will be asked to complete a Proctor Form.

- Tests are stored in a locked file until it is administered.

- Completed tests will be returned to the locked file with a written report which summarizes the services provided to the student, start, and stop time, etc.

*Late test requests that are received by staff may not be accommodated.

Testing conditions (e.g. open book, closed book) for students with disabilities should parallel those that you enforce in the classroom. Tests will be administered as “closed book, closed notes” unless otherwise specified by you. Use of calculators, spell check, etc. must be preapproved.

- extended time

- distraction reduced area

- use of a scribe

- audio recording of print material

- e-text conversion

- computer access (with or without technology software)

- large print

- live reading

- answer sheet completion and/or CCETV (closed-circuit enlarging television)

Academic honesty from students who use test accommodations is a fundamental expectation as it is for all UH Maui College students. Academic dishonesty by a student constitutes a serious violation of the Student Conduct Code. In the event of suspected academic dishonesty, the test will be terminated immediately, you will be notified of the incident, and all test materials will be returned to you with an incident report. Students are informed that this violation may result in their probation, suspension, or expulsion from the college.

Your invaluable cooperation is appreciated! Please contact the Disability Coordinator, Lisa Deneen, for any questions or concerns about test accommodations.

bottom of Providing Test Accommodations

BACK TO TOP

Note Taking and Note Takers

If a student at UHMC is eligible for and has requested note taking services, it will be indicated on the disability status letter delivered to you.

Note takers are UHMC students enrolled in your class who have been hired by our office to take complete notes for students with disabilities who have been approved to receive note taking services. Note takers are registered in the same class as students who need the notes and are expected to provide a copy of their notes to students with disabilities.

Each semester, the Disability Coordinator seeks out academically strong students who are good communicators, service-oriented, responsible, and respectful to serve as student note takers. It is not unusual for the Disability Coordinator to ask the student and/or faculty member to assist in identifying a qualified note taker for the class. We will let faculty know if such a request is necessary; however, faculty are encouraged to recommend students to the Disability Coordinator whom they believe may be qualified to work as note takers, and/or encourage such students to inquire about employment themselves.

Confidentiality is emphasized to our student-staff as students with disabilities may not want to be identified in class. Note takers are unaware about the nature of a student’s disability. They are informed that the student is eligible for note taking services and are given information in regards to the scope of their note taking assignment. Note takers often drop off notes at the Counseling Office where students later pick them up.

bottom of Note Taking and Note Takers

BACK TO TOP

Disability Awareness

APPROPRIATE LANGUAGE

- People with disabilities are people first. The Americans with Disabilities Act officially changed the way people with disabilities are referred to and provided the model. Refer to the person first, then the disability. This emphasizes the person and not the disability.

- Use the word disability when referring to someone who has a physical, mental, emotional, sensory, or learning impairment.

- Do not use the word handicapped. A handicap is what a person with a disability cannot do.

- Avoid labeling individuals as victims, disabled, or names of conditions. Instead, use people with disabilities or someone who has epilepsy.

- Avoid terms such as wheelchair bound. Wheelchairs provide access and enable individuals to get around. Instead, use a person who uses a wheelchair or someone with mobility impairment.

APPROPRIATE INTERACTION

- When introduced, offer to shake hands. People with limited hand use or artificial limbs can usually shake hands. It is an acceptable greeting to use the left hand for shaking.

- Treat adults as adults. Avoid patronizing people who use wheelchairs by patting them on the shoulder or touching their head. Never place your hands on a person’s wheelchair as the chair is a part of the body space of the user.

- Speak directly to the person with a disability. Do not communicate through another person. If the person uses an interpreter, look at the person and speak to the person, not to the interpreter.

- Offer assistance with sensitivity and respect. Ask if there is something you might do to help. If the offer is declined, do not insist.

- If you are a sighted guide for a person with a visual impairment, allow the person to take your arm at or above the elbow so that you guide rather than propel.

- When talking with a person with a speech impairment, listen attentively , ask short questions that require short answers, avoid correcting, and repeat what you understand if you are uncertain.

- When first meeting a person with blindness, identify yourself and any others who may be with you.

- When speaking to a person with a hearing impairment, look directly at the person and speak slowly. Avoid placing your hand over your mouth or turning your back to the person when speaking. Written notes may be helpful for short conversations.

bottom of Disability Awareness

BACK TO TOP

Understanding Disabilities and Structuring for Success

The University of Hawaii Maui College Disability Services is committed to assuring equal access to UHMC’s facilities, programs, services, and activities for students with disabilities. Our goal is to “structure for success” by:

- Providing reasonable academic accommodations to qualified students.

- Promoting an informed and hospitable learning community.

Our purpose is to meet the accessibility standards outlined under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Public Law 93-112) states that “no otherwise qualified individual with a disability in the United States shall solely by reason of his (or her) disability, be excluded from participation in, be denied benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance…” Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 provides for equal access and reasonable accommodations for otherwise qualified students with disabilities. Requirements common to these regulations include reasonable accommodations for employees with disabilities; program accessibility; effective communication for people who have hearing or vision disabilities; and accessible new construction and alterations.

*In relation to post-secondary and vocational education services, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 states, “an individual with a disability is further defined as a person who meets the academic and technical standards requisite to admission or participation in the recipient’s education program or activity.”

Hearing Disabilities

A hearing disability is any type or degree of auditory loss, while deafness is an inability to use hearing as a means of communication. Hearing loss may be sensorineural, involving an impairment of the auditory nerve; conductive, a defect in the auditory system which interferes with sound reaching the cochlea; or a mixed impairment, involving both sensorineural and conductive. Hearing loss is measured in decibels and may be mild, moderate, or profound. A person who is born with a hearing loss may have language deficiencies and exhibit poor vocabulary and syntax. Many students with hearing loss may use hearing aids, FM loop systems, and rely on lip reading. Others may require an interpreter.

HOW TO STRUCTURE STUDENTS WITH HEARING DISABILITIES FOR SUCCESS

- Speak while facing the class to provide speech-reading cues.

- Provide written supplements to oral instructions, assignments, and directions.

- Provide visual aids as often as possible.

- Make sure that audio materials are captioned, and turn on the captioning.

- Prior to viewing slides or movies, provide an outline or summary of the materials to be covered.

- When questions are asked from the class, repeat the questions before answering it.

- Be mindful about giving procedural information while handing out papers. Make sure such information is clearly understood by the student.

- Reduce excess noise as much as possible to facilitate communication.

bottom of Hearing Disabilities

BACK TO TOP

Learning Disabilities

A learning disability is a permanent neurological disorder that affects the manner in which information is received, organized, remembered, and then retrieved or expressed. Students with learning disabilities possess average to above average intelligence. The disability is demonstrated by a significant discrepancy between expected and actual performance in one or more of the basic functions: memory, oral expression, listening comprehension, written expression, basic reading skills, reading comprehension, mathematical calculation, and mathematical reasoning.

Learning disabilities vary from one person to another and are often inconsistent within an individual. Some of the terms associated with learning disabilities include:

- Auditory Figure-Ground Perception – inability to hear one sound among others

- Figure-Ground Perception – inability to see an object from a background of other objects

- Dyscalculia – difficulty with mathmematics

- Dysgraphia – difficulty in writing words with appropriate syntax

- Dyslexia – difficulty with reading

- Dysphasia – difficulty with speaking fluently or understanding others

- Dyspraxia – difficulty with planning a sequence of coordinated movements or difficulty with executing a plan

- Non-Verbal Learning Disorder – difficulty with motor coordination, visual-spatial organization, and/or lack of social skills

- Visual Discrimination – difficulty with seeing the differences in objects

- Auditory Sequencing – inability to hear sounds in the right order

- ADD, ADHD, ADD/ADHD – inattention, impulsivity, easily distractible, and sometimes hyperactivity

A Learning Disability is NOT . . .

- A form of mental retardation or an emotional disorder.

Students may demonstrate one or more problem characteristics and the form may be mild, moderate, or severe.

STUDY SKILLS

- inability to organize and budget time

- difficulty taking notes/outlining material

- difficulty following directions

- difficulty completing assignments on time

WRITING SKILLS

- frequent spelling errors

- incorrect grammar

- poor penmanship

- poor sentence structure

- difficulty taking notes while listening to class lectures

- problems with organization, development of ideas and transition words

ORAL LANGUAGE

- difficulty understanding oral language when lecturer speaks fast

- difficulty attending to long lectures

- poor vocabulary and word recall

- problems with correct grammar

- difficulty in remembering a series of events in sequence

- difficulty with pronouncing multi-syllabic words

READING SKILLS

- slow reading rate

- inaccurate comprehension

- poor retention

- poor tracking skills (skip words, loose place, miss lines)

- difficulty with complex syntax on tests

- incomplete mastery of phonics

MATH SKILLS

- computational skill difficulties

- difficulty with reasoning

- difficulty with basic math operations (multiplication tables)

- number reversals, confusion of symbols

- difficulty copying problems

- difficulty with concepts of time and money

SOCIAL SKILLS

- poor eye contact

- spatial disorientation

- low frustration level

- low self-esteem

- impulsive

- disorientation in time

- difficulty with delaying problem resolution

- inability to read social cues

HOW TO STRUCTURE STUDENTS WITH LD FOR SUCCESS

- Provide a detailed course syllabus.

- Clearly spell out expectations before course begins (e.g., grading, material to be covered, due dates).

- Start each lecture with an outline of material to be covered that period. Briefly summarize key points at the conclusion of class.

- Speak directly to students, and use gestures and natural expressions to convey further meaning.

- Present new or technical vocabulary visually (whiteboard, handout, etc.) and orally. Terms should be used in context to convey meaning.

- Use visual aids to augment the spoken language. If there is a deficit in one modality, the student may be able to learn more readily through another.

- For students who use alternative text, announce reading assignments well in advance to allow for conversion time.

- Permit use of simple calculators, scratch paper, and spellers’ dictionaries during exams.

- Provide study questions for exams that demonstrate the format as well as the content of the test. Explain what makes an answer “good” and why.

bottom of Learning Disabilities

BACK TO TOP

Orthopedic/Mobility Disabilities

A variety of orthopedic/mobility-related disabilities may result from congenital conditions, accidents, or progressive neuromuscular diseases. These disabilities include conditions such as spinal cord injury (paraplegia or quadriplegia), cerebral palsy, spina bifida, amputation, muscular dystrophy, cardiac conditions, cystic fibrosis, paralysis, polio/post-polio, and stroke. Functional limitations and abilities vary widely even within one group of disabilities. Accommodations vary greatly and can best be determined on a case-by-case basis.

HOW TO STRUCTURE STUDENTS WITH O/M DISABILITIES FOR SUCCESS

- Allow extra travel time to class.

- Provide adequate aisle access and special seating.

- Allow extra time for assignments due to slow writing speed.

- Provide adjustable lab tables or drafting tables in lab settings.

bottom of Orthopedic/Mobility Disabilities

BACK TO TOP

Psychological Disabilities

Psychological disabilities cover a wide range of disorders such as depression, anxiety, post traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, and personality disorders. The majority of psychological disabilities are controlled using a combination of medications and psychotherapy. Some of the following accommodations may be considered appropriate and reasonable.

HOW TO STRUCTURE STUDENTS WITH PSYCHOLOGICAL DISABILITIES FOR SUCCESS

- Allow extended time and/or distraction reduced area for testing.

- Allow note takers or tape recorders in class.

- Flexibility in the attendance requirements in cases of health related absences. (Students are required to make up missed assignments and tests.)

- Allow “incomplete” or “late withdrawal” status in case of a course failure due to prolonged illness.

bottom of Psychological Disabilities

BACK TO TOP

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Traumatic brain injury is the term used in reference to brain damage caused by some extrinsic agent. There is a wide range of differences in the effects of a TBI on the individual, but most cases result in some type of impairment. Functions that may be affected include: memory, cognitive/perceptual communication, impulse control, motor abilities, sensory perception, and physical abilities.

Students with TBI may demonstrate one or more functional limitations and the form may be mild, moderate, or severe:

- organizing thoughts, cause-effect relationships, and problem solving

- processing information and word retrieving

- generalizing and integrating skills

- interacting with others

- exhibiting discrepancies in abilities such as reading comprehension at a much lower level than spelling ability

HOW TO STRUCTURE STUDENTS WITH TBI FOR SUCCESS

- Establish a routine. Students with TBI do not deal well with the unexpected.

- Announce assignments well in advance. Students with TBI require more time to process and master new information.

- Use visual aids to augment the spoken language. If there is a deficit in one modality, the student may be able to learn more readily through another.

- Use non-timed activities to render a more accurate measure of the student’s grasp of key concepts and mastery of course materials.

- Consider allowing for notes during testing or chunking tests into smaller segments taken over a period of time to accommodate memory impairments.

bottom of Understanding Disabilities and Structuring for Success; Traumatic Brain Injury

BACK TO TOP

Accessibility

Accessibility is a general term used to describe the degree to which a product, device, service, or environment is available to as many people as possible. It can be viewed as the “ability to access” and benefit from some system or entity. Accessibility is often used to focus on people with disabilities or special needs and their right of access to entities, often through use of assistive technology.

Accessibility is not to be confused with usability which is used to describe the extent to which a product (e.g., device, service, environment) can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use.

Accessibility is strongly related to universal design when the approach involves “direct access”. This is about making things accessible to all people (whether they have a disability or not). An alternative is to provide “indirect access” by having the entity support the use of a person’s assistive technology to achieve access (e.g., screen readers).

The term “accessibility” is also used in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities as well as the term “universal design.”

The following checklist can be used to ensure content is accessible at a basic level:

- Text Documents

- can be highlighted, copied, and pasted

- are saved as Word (.doc), accessible PDF (.pdf), or RTF (.rtf)

- are made with style sheets and headings with appropriate bullet points instead of dense text

- Power Point Presentation Slides

- were created using standard templates (you did not insert “text” boxes)

- include text descriptions for all graphics and pictures

- are set up with an easy to follow outline to keep students organized

- are formatted with the same colors and structure to make them easy to follow

- Images

- include text descriptions as captions or “alt” tags

- are described in the text as much as possible

- are not the only way students will learn pertinent information required for the course

- Webpages

- were written up to the current W3C and HTML 5 standards

- have an obvious structure

- include easy-to-read text, good contrast, and are not too busy

- Video and Audio

- includes captions or transcripts

- are kept to a reasonable length

bottom of Accessibility

BACK TO TOP

Creating Accessible PDFs

Adobe’s Portable Document Format (PDF) is widely used in distributing documents on campus. While it is possible to make most PDF files accessible for users with disabilities, it is generally much easier to make HTML web pages accessible, and HTML is more widely supported by assistive technologies. Also, certain content (such as mathematical and scientific notation) cannot currently be made accessible in PDF files. Therefore, the first consideration related to PDF accessibility must always be this:

Is PDF necessary for my document, or could I communicate the same information using an HTML web page?

If your answer to the above question is, “Yes, PDF is necessary,” it is important to follow certain steps in order to create a PDF that is accessible. It is also possible to correct accessibility problems post-production using Adobe Acrobat Professional. This page contains workflows for both situations.

MAKING A PDF ACCESSIBLE FROM SCRATCH

-

- Use authoring tools that support accessible tagged PDF (e.g., Microsoft Word in Windows).

- Follow best practices for authoring documents that are accessible:

- Use built-in styles for headings.

-

- Add alt text to images (In Office 2010 and 2011, use Description field–not Title.).

- For data tables, explicitly identify the header row (In Word, do this in Table Properties.).

- Export to Tagged PDF–see below.

EXPORTING FROM WORD TO TAGGED PDF

-

- In Word 2003 and 2007 (Windows), this requires the Adobe PDF Maker Plugin (This ships with Adobe Acrobat.).

-

- In Word 2010 (Windows), simply Save As PDF (Word 2011 for Mac does not produce an accessible, tagged PDF.).

- When saving, select Options and be sure that “document structure tags for accessibility” is checked (This is checked by default, but will be unchecked if you select “Minimize Size” and will need to be rechecked.).

CREATING AN ACCESSIBLE TAGGED PDF FROM ADOBE INDESIGN

The following steps apply to InDesign CS5.5. Documents created using CS4 and earlier versions of InDesign require accessibility repair using Adobe Acrobat Pro (see the next section).

-

- Create your document using paragraph styles (Window > Styles > Paragraph Styles). These aren’t just a good idea–they’re required for accessibility. Use them consistently throughout the document to define styles for all text, including headings and sub-headings. For headings, use styles that indicate the heading level (e.g., Heading1, Heading2) within the organizational structure of the document (Headings should form an outline of the document.).

-

- Associate each of the styles you’ve created with specific PDF tags. From the Paragraph Styles options menu, select Edit All Export Tags, check the PDF radio button, then select the relevant tags for each of your styles.

-

- Add alt text to images (Object > Object Export Options > Alt Text).

-

- Establish content read order with the Articles panel (Window > Articles). Simply drag content from the document into the Articles panel in the order in which it should be read by screen readers. To drag multiple items, select them in the correct read order using Shift + click, then drag them all at once to the Articles panel.

- Export to PDF, be sure to select “Acrobat 6″ or higher for compatibility, and check the “Create Tagged PDF” checkbox.

Additional details about each of these steps are available in Adobe’s white paper New Solutions for Creating Accessible PDF Documents with Adobe InDesign CS5.5 (in PDF) and on the Adobe InDesign CS5.5 Accessibility website.

PDF DOCUMENT ACCESSIBILITY REPAIR WORKFLOW USING ADOBE ACROBAT

NOTE: Modifying PDFs can have unpredictable results, and there is no “Undo”. Save often (Saving multiple versions is recommended.)!

- Does the document have text?

- If not, convert to text (View > Tools > Recognize Text).

- Is the document tagged? (Ctrl+D, “Description” tab)

- If not, add tags (View > Tools > Accessibility > Add Tags To Document).

- Does the document need to be touched up? (View > Tools > Accessibility > Touch Up Reading Order).

- Click decorative or redundant images, then click “background.”

- Add alt text to remaining images (right click on image > edit alt text).

- Rearrange order if needed (click “show order panel” > drag items).

- Are headings marked up as headings at appropriate levels?

- Determine visually what the heading structure should be.

- View > Show/Hide > Navigation Panes > Tags

- Use PDF text selector to highlight headings.

- In Tag pane, select “Find Tag from Selection”.

- To change tag, right click, select Properties, and enter Alternate Text.

- Does other markup need to be fixed?

- Delete tag and start over from scratch.

- Are URLs encoded as links?

- Document Processing > Create Links from URLs.

- Is the language of the document defined?

- File > Properties > Advanced > Language

- Check for any lingering errors.

- Tools > Accessibility > Full check

PDF FORM ACCESSIBILITY REPAIR WORKFLOW USING ADOBE ACROBAT

- Is the form interactive?

- If not, proceed to Creating Accessible PDF Forms using Acrobat Pro.

- Is the tab order intuitive?

- If not, correct it (Tools > Forms > Edit, play with Tab Order; select “Close Form Editing” when finished).

- Are all text fields appropriately labeled? How to tell:

- Tools > Forms > Edit; look in Properties for ToolTip of each field, or

- Tab through form using Read Out Loud (View > Read Out Loud > Activate Read Out Loud)

- To fix labels on text fields:

- Right click on field; select Properties

- Enter a detailed, easy-to-understand prompt as Tooltip

- Are radio buttons appropriately grouped and labeled?

- All radio buttons in a set should have the same name.

- Tooltip is the overall prompt for the set (similar to legend in HTML).

- Labels for individual radio buttons within the set are defined using the Button Value field in the Options tab.

- Are checkboxes appropriately labeled?

- Checkboxes can’t be grouped like radio buttons. The workaround is to be sure the prompt for the overall set of checkboxes is clear within the tooltip for each option (For example, “Favorite Food: Tofu”, “Favorite Food: Steak”, “Favorite Food: Pizza”, etc.).

- Are checkboxes appropriately labeled?

- Tools > Document Processing > Create Links from URLs

- Tools > Accessibility > Add Tags To Document

- Repair tags as needed.

- Tools > Accessibility > Full Check

CREATING ACCESSIBLE PDF FORMS USING ADOBE ACROBAT PRO

- Do not create an interactive form using the original authoring tools form features.

- Do not create a tagged PDF.

- Use Acrobat Pro to make form fields interactive. Here’s how:

- Automatically detect and markup form fields (Tools > Forms > Create).

- Manually add/edit and form fields that weren’t correctly detected

- Check tab order; repair if needed.

- Check all labels (tooltips); repair if needed.

- Check group labels and options for radio buttons; repair if needed.

- Check labels for checkboxes; repair if needed.

CREATING ACCESSIBLE PDF FORMS USING ADOBE LIVECYCLE DESIGNER

Some people prefer using LiveCycle Designer for creating PDF forms. It is fairly easy and intuitive, and has many more features for creating robust interactive forms. The pros and cons of each are beyond the scope of this document, but there are other sources for this information, including Adobe’s Acrobat versus LiveCycle Designer.

If you choose to create forms using LiveCycle Designer, here are some things to keep in mind related to accessibility:

- Tags in LiveCycle Designer forms cannot be edited using Adobe Acrobat Pro.

- LiveCycle Designer’s built-in templates should not be used. They include untagged inaccessible content that cannot be corrected.

- The Basic Workflow:

- Start with a blank document.

- Drag form fields and other content as needed into the document.

- Be sure to include a tooltip for all fields.

- LiveCycle Designer additionally has an option for “Custom Screen Reader Text”. Screen readers won’t read both this text and the tooltip, so if you use both be sure they stand alone.

- Save as PDF.

TEST THE PDFs ACCESSIBILITY

- Follow these steps in Adobe Reader (a free download) or Adobe Acrobat to hear the text read aloud.

- Click on the “View” pull-down menu; Read Out Loud; Activate Read Out Loud, followed by the “View” pull-down menu; Read Out Loud; Read This Page Only.

- If the document reads aloud, but the text is read out of order, adding “tags” to the document may help. In Adobe Acrobat, choose “Advanced” > Accessibility > Add Tags to Document. (This command adequately tags most standard layouts so text-to-speech software reads the PDF in the correct order, but it cannot always correctly interpret the structure and reading order of complex page elements.)

CREATING ACCESSIBLE PDFs USING ADOBE ACROBAT (short version)

- Adobe Acrobat/Professional is capable of converting many different types of files into an accessible PDF. If you have a document scanned as a GIF, JPEG, PNG, TIFF, or Microsoft Office file, any of these can be made accessible for your students.

- Keep in mind that if the original scan is blurry, the OCR programs will not be able to decipher the words and the document cannot be read aloud.

- Some, though not all, PDFs downloaded from online databases, journals, or publishers may already be in an accessible format. Test the file by following the steps above – you may not have to run an OCR scan.

*This works on Windows 7 and on Windows XP; it may not read on Windows Vista.

*Source: University of Washington – http://www.washington.edu/accessibility/pdf/

bottom of Creating Accessible PDFs

BACK TO TOP

Universal Design

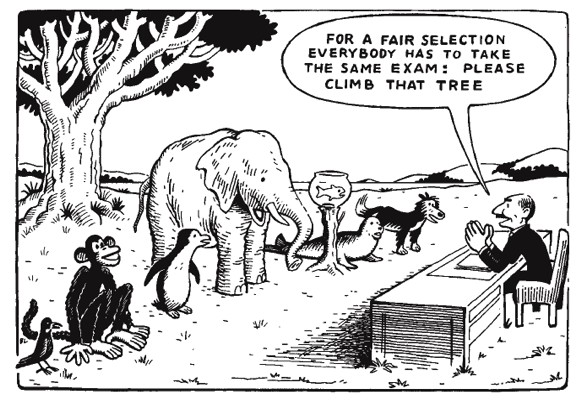

Universal Design is a design approach that seeks to create environments, objects, and systems that can be used by as many people as possible. To this end, Universal Design is the process of embedding choice for all people in the things we design.

- Choice involves flexibility and multiple, alternative means of use and/or interface.

- People include the full range of people regardless of age, ability, sex, economic status, etc.

- Things include spaces, products, information systems and any other things that humans manipulate or create.

Universal Design is a user-centered process that evolves as designers and users broaden their own understanding, perspectives and experience by working with the range of users in a variety of environments. The more you know about the subject, the more you realize there is to learn about it. As such, Universal Design is like the horizon: it recedes as you move towards it.

Universal Designing is a lifelong learning opportunity and process. We become better Universal Designers as we learn more about people and the choices they may wish to exercise as they interact with the environments in which they operate. Because of this, no one knows it all. We can all learn from each other about how to better design things for all people. In this lifelong learning sense, we are all students of Universal Design.

The term “Universal Design” has evolved from “Barrier Free Design”, “Accessible Design”, “Trans-generational Design”, and “Adaptable Design”. It is now considered to be synonymous with “Design for All” and “Inclusive Design”.

You do not need to redesign your entire course; however, you are asked to include in your design students who are diverse in age, learning styles, language, and who may have disabilities. You may be surprised to find that the practical applications of universal design may benefit other students in your class.

- Equitable Use. The design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities. For example, a course website that is designed so that it is accessible to everyone, including students who are blind and using text-to-speech software, employs this principle.

- Flexibility in Use. The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities. An example is a museum that allows a visitor to choose to read or listen to the description of the contents of a display case.

- Simple and Intuitive. Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level. Science lab equipment with control buttons that are clear and intuitive is a good example of an application of this principle.

- Perceptible Information. The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities. An example of this principle being employed is when multimedia projected in a noisy academic conference exhibit includes captioning.

- Tolerance for Error. The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions. An example of a product applying this principle is educational software that provides guidance when the student makes an inappropriate selection.

- Low Physical Effort. The design can be used efficiently and comfortably, and with a minimum of fatigue. Doors that are easy to open by people with a wide variety of physical characteristics demonstrate the application of this principle.

- Size and Space for Approach and Use. Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation and use regardless of the user’s body size, posture or mobility. A science lab work area designed for use by students with a wide variety of physical characteristics and abilities is an example of this principle.

Many teaching strategies that assist students with disabilities are known to also benefit nondisabled students. Instruction that is provided in an array of approaches will reach more students than instruction using one method. The following are teaching strategies that will benefit students in the academic setting:

Required Text

- Select a text with a study guide.

Before the Lecture

- Write key terms or an outline on the board or prepare a lecture handout.

- Create study guides.

- Assign advance readings before the topic is due in the class session.

- Give students questions that they should be able to answer by the end of each lecture.

During the Lecture

- Briefly review the previous lecture.

- Use visual aids such as overheads, diagrams, charts and graphs.

- Allow the use of tape recorders.

- Emphasize important points, main ideas and key concepts.

- Face the class when speaking.

- Explain technical language and terminology.

- Speak distinctly and at a relaxed rate pausing to allow students time for note taking.

- Leave time for questions periodically.

- Give assignments in writing as well as orally.

Grading and Evaluation

- Consider a variant grading system with multiple grades for various tasks weighted differently.

- Work with the student to make arrangements early for testing accommodations that involve readers/scribes.

*Please contact the Disability Coordinator if you need any assistance.

bottom of Universal Design

end of Information for Faculty page

BACK TO TOP